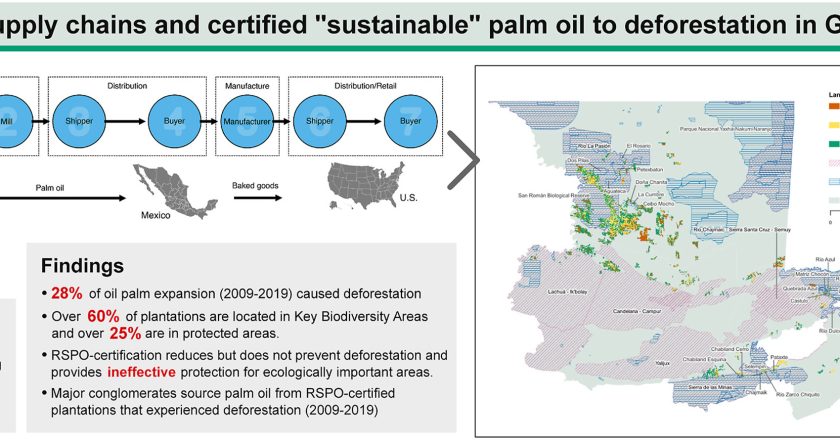

- The transformation of ancestral lands into intensive monoculture plantations has led to the destruction of Guatemala’s native forests and traditional practices, as well as loss of livelihoods and damage to local health and the environment.

- A network of more than 40 Indigenous and local communities and farmer associations are developing agroecology schools across the country to promote the recovery of ancestral practices, educate communities on agroecology and teach them how to build their own local economies.

- Based on the traditional “campesino a campesino” (from farmer to farmer) method, the organizations says it has improved the livelihoods of 33,000 families who use only organic farming techniques and collectively protect 74,000 hectares (182,858 acres) of forest across Guatemala.

Every Friday at 7:30 a.m., María Isabel Aguilar sells her organic produce in an artisanal market in Totonicapán, a city located in the western highlands of Guatemala. Presented on a handwoven multicolor blanket, her broccoli, cabbage, potatoes and fruits are neatly organized into handmade baskets.

Aguilar is in a cohort of campesinos, or small-scale farmers, who took part in farmer-led agroecology schools in her community. As a way out of the cycle of hunger and poverty, she learned ecological principles of sowing, soil conservation, seed storage, propagation and other agroecological practices that have provided her with greater autonomy, self-sufficiency and improved health.

“We learned how to develop insecticides to fend off pests,” she said. The process, she explained, involves a purely organic cocktail of garlic, chile, horsetail and other weeds and leaves, depending on what type of insecticide is needed. “You want to put this all together and let it settle for several days before applying it, and then the pests won’t come.”

“We also learned how to prepare fertilizer that helps improve the health of our plants,” she added. “Using leaves from trees or medicinal plants we have in our gardens, we apply this to our crops and trees so they give us good fruit.”

The expansion of large-scale agriculture has transformed Guatemala’s ancestral lands into intensive monoculture plantations, leading to the destruction of forests and traditional practices. The use of harmful chemical fertilizers, including glyphosate, which is prohibited in many countries, has destroyed some livelihoods and resulted in serious health and environmental damage.

To combat these trends, organizations across the country have been building a practice called campesino a campesino (from farmer to farmer) to revive the ancient traditions of peasant families in Guatemala. Through the implementation of agroecology schools in communities, they have helped Indigenous and local communities tackle modern-day rural development issues by exchanging wisdom, experiences and resources with other farmers participating in the program.

Keeping ancestral traditions alive

The agroecology schools are organized by a network of more than 40 Indigenous and local communities and farmer associations operating under the Utz Che’ Community Forestry Association. Since 2006, they have spread across several departments, including Totonicapán, Quiché, Quetzaltenango, Sololá and Huehuetenango, representing about 200,000 people — 90% of them Indigenous.

“An important part of this process is the economic autonomy and productive capacity installed in the communities,” said Ilse De León Gramajo, project coordinator at Utz Che’. “How we generate this capacity and knowledge is through the schools and the exchange of experiences that are facilitated by the network.”

Utz Che’, which means “good tree” in the K’iche’ Mayan language, identifies communities in need of support and sends a representative to set up the schools. Around 30-35 people participate in each school, including women and men of all ages. The aim is to facilitate co-learning rather than invite an “expert” to lead the classes.

The purpose of these schools is to help farmers identify problems and opportunities, propose possible solutions and receive technical support that can later be shared with other farmers.

The participants decide what they want to learn. Together, they exchange knowledge and experiment with different solutions to thorny problems. If no one in the class knows how to deal with a certain issue, Utz Che’ will invite someone from another community to come in and teach.

“We identify a producer who has specific experience in a subject — for example, potato production, pig production or seed reproduction — and through this process, we transfer knowledge between farmers,” Gramajo said.

Attendance is free. However, as part of the process, former students are responsible for supporting the next cohort of farmers, by offering technical support and guidance. The process replicates the natural passing down of knowledge through generations of farmers, hence its name campesino a campesino.

Nils McCune, an agroecological researcher at the University of Vermon, said this type of approach “starts with the recognition that farmers are the best teachers of farmers.”

Like agroecology schools organized by the Landless Workers Movement in Brazil (or MST, its acronym in Portuguese), classes are both theoretical and practical. However, the Guatemalan schools take place on participants’ farms rather than on a formal campus.

Gramajo pointed to Florinda Dominga Par, from a community called Chuicaxtun, who has been in the program since 2014.

“In the schools, she learned how to produce bokashi fertilizer,” a composting method that involves fermenting organic manure, “which has become her greatest ally for potato production,” said Gramajo. “Today, she is one of the best producers of organic potatoes.”

Farmers can also learn about the selection and protection of native seeds, the planting and agricultural management of their crops, soil conservation and rainwater harvesting for irrigation or animals.

Caterina Tzic Canastuj, another producer who has participated in the schools, told Mongabay she learned how to create an organic fertilizer called chitosan, which protects her tomatoes against harmful microorganisms, resulting in much larger, high-quality yields.

Part of what Utz Che’ does is document ancestral practices to disseminate among schools. Over time, the group has compiled a list of basics that it considers to be fundamental to all the farming communities, most of which respond to the needs and requests that have surfaced in the schools.

Agroecology schools transform lives

Claudia Irene Calderón, based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is an expert in agroecology and sustainable food systems in Guatemala. She said she believes the co-creation of knowledge is “key to balance the decision-making power that corporations have, which focus on profit maximization and not on climate change mitigation and adaptation.”

“The recovery and, I would add, revalorization of ancestral practices is essential to diversify fields and diets and to enhance planetary health,” she said. “Recognizing the value of ancestral practices that are rooted in communality and that foster solidarity and mutual aid is instrumental to strengthen the social fabric of Indigenous and small-scale farmers in Guatemala.”

Through the implementation of agroecology schools across the country, Utz Che’ says it has improved the livelihoods of 33,000 families. In total, these farmers also report that they collectively protect 74,000 hectares (182,858 acres) of forest across Guatemala by fighting fires, monitoring illegal logging and practicing reforestation.

In 2022, Utz Che’ surveyed 32 women who had taken part in the agroecology school. All the women had become fully responsible for the production, distribution and commercialization of their products, which was taught to them in agroecology schools. Today, they sell their produce at the artisanal market in Totonicapán.

The findings, which highlight the many ways the schools helped them improve their knowledge, also demonstrate the power and potential of these schools to increase opportunities and strengthen the independence of women producers across the country.

View related coverage of agroecology schools in Brazil and India

For McCune, agroecology, shared through a social process like campesino a campesino, results in healthier food using less land, all while reducing the harmful impacts of intensive agriculture on the health, water and food sources of communities.

“It is probably the most clearly successful of any methods for mobilizing agroecological knowledge,” he said. “However, as a social process, campesino a campesino has to swim in the turbulent waters of changing sociopolitical contexts.”

As Gramajo pointed out, one of the greatest challenges they face is the lack of support from governments that lean toward agricultural models that aim to maximize profit at the expense of rural communities.

“There are several agreements and international treaties to support farmers in Guatemala, but these are not respected,” she said. “This is a big challenge.”

Although some of the advances of the agricultural industry’s expansion in Guatemala have been useful, such as the development of more efficient irrigation systems, post-harvest technologies and a greater understanding of plant-pathogen interactions, “the optimization of the systems to focus solely on the maximization of production is risky,” said Calderón, adding, “it has been shown to have very negative environmental and social impacts.”

Gramajo said the schools focus on “activities that strengthen the economy of the families and reduce the threats that are generated from the exploitation of natural resources, such as the deforestation that’s carried out in some areas to clear space for monocultures and the advancement of the agricultural industry.”

The schools are centered around the idea that people are responsible for protecting their natural resources and, through the revitalization of ancestral practices, can help safeguard the environment and strengthen livelihoods.